- October 01, 2025

- By Jennifer S. Holland

As the Civil War ramped up, a leading abolitionist of the day looked at the man leading the Union and didn't like what he saw: hesitancy and a lack of commitment to ending the enslavement of Black Americans.

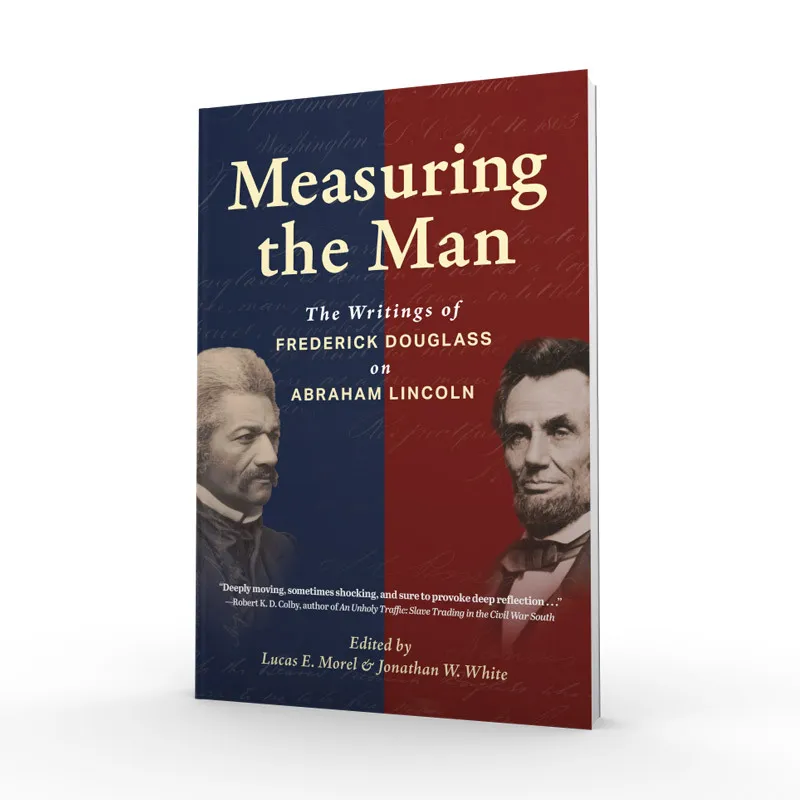

How Marylander Frederick Douglass revised his view of Abraham Lincoln, long celebrated as perhaps our greatest president, is a key theme running through a new anthology by University of Maryland alum Jonathan White M.A. '03, Ph.D. '08 and Lucas Morel. “Measuring the Man: The Writings of Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln,” published Wednesday by Reedy Press, includes 12 newly discovered letters and speeches and illustrates the complexity of this historic relationship.

White, a historian, has written or edited 20 books, including “A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House,” awarded the 2023 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize for the best scholarly work on the 16th president’s legacy. Speaking to Maryland Today, he recalled the thrill of discovering new details about Douglass’ mindset and discussed how the famed orator and statesman’s change of heart fits into an extraordinary chapter of American history.

What’s the central story of the book?

It’s a story about changing perspectives. Frederick Douglass was highly critical of Lincoln at the beginning of the Civil War. As an ex-slave, he felt the president was not freeing slaves quickly enough, not fighting hard enough for Black equality. But after three personal interactions with Lincoln, he came to appreciate the political constraints on the president’s actions and saw that Lincoln truly had a deep desire to see Black people free. Most of what Douglass wrote about Lincoln after 1865 was very positive.

What was it like uncovering previously unknown documents for the book?

One fun thing about being a historian in the 21st century is that millions and millions of newspaper pages have been digitized and are easily accessible online. Sometimes information is hiding in plain sight. It’s most thrilling when you find something new and immediately realize its importance. In this case I think the discovered documents, including Douglass’s personal letters, will change how people think about the significance of the relationship between Douglass and the president.

Was there anything surprising in the discoveries?

Douglass was a diehard abolitionist, but in a letter in 1864, his practical side comes to light. He writes that despite a preference for a radical third-party candidate named John C. Frémont, he would support Lincoln’s run for a second term. “[Frémont] is the fittest man, but has the fewest supporters,” he wrote, “and though one man in the right is a majority against the whole world wrong, at the polls, numbers rule. A candidate without a party may be sublime, but he cannot be successful.” This was a remarkable admission of compromise for a radical like Douglass.

Even more surprising: In 1865, while mourning the assassinated Lincoln, whom he considered a personal friend, Douglass made a startling statement: He admitted that Lincoln’s death might be good for securing Black freedom and equality. Douglass believed Lincoln was “too much under the dominion of his amiable qualities” to get the job done and would have been too forgiving of the white South. He hoped that as president, Andrew Johnson, who had proclaimed, “I will indeed be your Moses” to a Black crowd in Nashville, would better answer “the stern requirements of the hour.” Other radicals had expressed similar views, but never Douglass.

What do you hope readers take away from this anthology?

Frederick Douglass was a complex guy; he was a purist who came to appreciate the value of being practical. At the same time, he worried about what would happen after the war: Would the Emancipation Proclamation become inoperative? And so, although he abhorred suffering, he didn’t want the war to end until the Constitution was amended to ensure full equality for all regardless of race. He was that focused on his cause that war was preferable to him than the chance of losing ground in the fight for equality and freedom.

(Book cover courtesy of Reedy Press)

Topics

People